It is now over 30 years since Britain’s intelligence agencies came out of the cold, first with the avowal of the Security Service (MI5) in 1989, and then the Secret Intelligence Service (SIS aka MI6) and the Government Communications Headquarters (GCHQ) in 1994. The creation that same year of the Intelligence and Security Committee marked a watershed moment. Since that point we have witnessed the gradual, if piecemeal, opening of official archives, the publication of several authorised and official histories of different intelligence organisations, the advent of annual speeches by the heads of the three main agencies, and the first forays into official social media accounts. In a grown-up democracy, transparency is necessary and important; just as significant as recognising that it can only ever go so far, and that secrecy must remain at the heart of intelligence work.

It was back in the mid-1980s that the Cambridge historian, Christopher Andrew, adopted Sir Alexander Cadogan's phrase, that intelligence was the ‘missing dimension’ of international relations, as the title of a volume, which he edited with David Dilks. They noted the challenge Cadogan's observation posed to scholars: that they should examine the role and significance of intelligence in policy decisions, something that laid the foundation for intelligence studies in the UK. Whilst gaps remain, of course, it would be difficult to make that same argument today, even if it remains more challenging to study the history of British intelligence compared to the United States. Archival releases in the UK are inconsistent at best: SIS does not release anything; MI5 records go up to the 1960s; GCHQ releases end a little earlier; Joint Intelligence Committee (JIC) records extend to the early 1980s; whilst Defence Intelligence records have been released incoherently. The result is that we have a much better grasp of the role of intelligence in the UK in the twentieth century, albeit one rife with varying blank spots.

Beyond the end of the Cold War there is even less to rely upon, but scholarship is buoyed by the changes in government approach that took place from 2008 onwards. In the first ever National Security Strategy, written by the Gordon Brown government, ‘intelligence’ became more integrated into conceptions of ‘national security’, whereby the nature of the twentieth century existential threats (largely Soviet Russia and Nazi Germany) were replaced by the threats from international Islamist terrorism. These didn’t target the country per se, but rather the way of life of those living in the UK. The result was a step change in security conception, whereby intelligence became somewhat synonymous with risk and resilience, packaged together into broader notions of ‘national security’. The point here is that the British government has arguably enlarged its conception of ‘intelligence’ to be much broader and encompass other areas. This is yet to be recognised in the academic study of intelligence, largely because of its historical orientation in the UK. Yet, as we shall see below, this is beginning to change.

The governmental shift to a broader definition is evident in the recently published 2025 Cabinet Office document ‘Guide to the UK National Security Community’. This unclassified, freely available document, has barely been spotted in the wild and although it really does little more than describe different elements of government, its unique value is in the definition of the composition of the United Kingdom Intelligence Community (UKIC) and the UK National Security Community. The UKIC, we are officially informed, comprises SIS, GCHQ, MI5, Defence Intelligence, National Cyber Force, the Joint Intelligence Organisation and National Security Secretariat in the Cabinet Office, and the Home Office’s Homeland Security Group. By contrast, the national security community is far broader and includes virtually all departments of state that might, at one time or another, receive intelligence and have a remit that might include ‘national security’. These range from the obvious large departments like the Ministry of Defence, Foreign Office and Home Office, through to the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, to the Welsh and Scottish Governments.

How, then, have these changes in practice been reflected in the world of scholarship and the academic study of intelligence? Within the King’s Centre for the Study of Intelligence (KCSI) we compile a database entitled IntelArchive. This is the foremost resource of its kind, and currently includes over 8,000 publications on intelligence (in its widest sense), drawn from around the world from the 1980s onwards. This database can be interrogated to identify trends in scholarship, and the results are revealing. Whereas in the past most academic scholarship was primarily historical in focus, it also was concentrated predominantly on the United States (by virtue of the fact that it has, historically, been more open with archival releases and the publication of memoirs). What is clear is that this pattern is beginning to change. The results from IntelArchive are fascinating:

- Surveying the breadth of scholarship, there are three main categories of focus: publications on national systems of intelligence, on the Cold War period, and on World War Two.

- Looked at a different way, more recently (as opposed to cumulatively) there have been increases in the volume of publications looking at intelligence in literature and popular culture; in Signals Intelligence (‘sigint’ across all time periods), and the Cold War period.

- In general, the pace of publications is growing extremely rapidly, with virtually double the number of publications produced in 2022 compared to 2016, and nearly double the amount in 2024 compared to 2022. Certainly, it is a subject matter that shows no sign of slowing.

- Most of these publications are in the form of journal articles (although, the database doesn’t distinguish between peer-reviewed articles and those in think-tank journals).

- The US remains the most studied country, followed by the UK and then Russia. Whilst the top ten most popular countries for attention are fairly unsurprising, there is an increasing volume of material on smaller states in Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere, including Lesotho, Eswatini, and Mongolia.

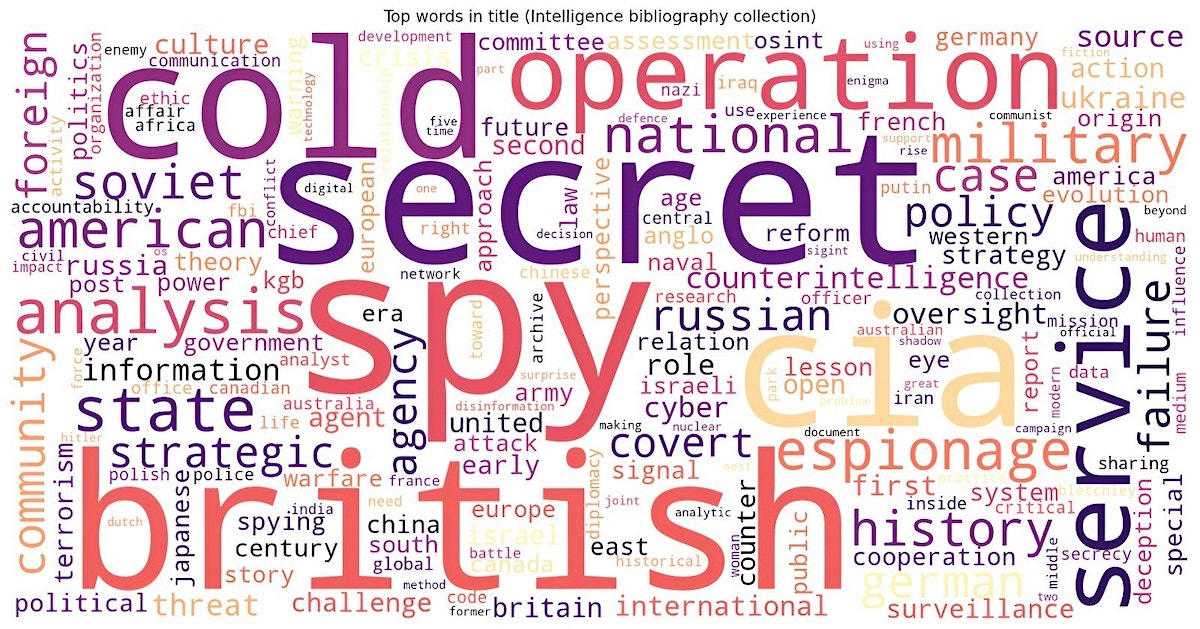

As a constantly evolving source that can be interrogated in various ways, the IntelArchive is well worth a look. The totality of the 8,200 sources reveals the following world cloud:

What is less obvious here are two things: firstly, that whilst the overwhelming majority of work is based upon either archival or empirical scholarship, there is a small but significant focus on abstract and theoretical publications; that ‘intelligence’ is not defined in the database but rather is explicit in the volume of publications and that, therefore, the 2008-onwards blurring of intelligence and national security isn’t entirely reflected. Expanding government definitions of ‘intelligence’ will need to make their way further into the academic field. There is some evidence of this in the manner in which the study of intelligence is expanding beyond history departments to more social science-focused disciplines. Moving forwards there is one thing that is absolutely certain: the work of the intelligence agencies is going to remain central to government work, but also as a mainstay of scholarship.

This article was first published in the internal HMG publication, the PHIA Newsletter (September 2025).

Photo by Hannah Reding on Unsplash